“For I have known them all already, known them all:

Have known the evenings, mornings, afternoons,

I have measured out my life with coffee spoons”

—T.S. Eliot “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”

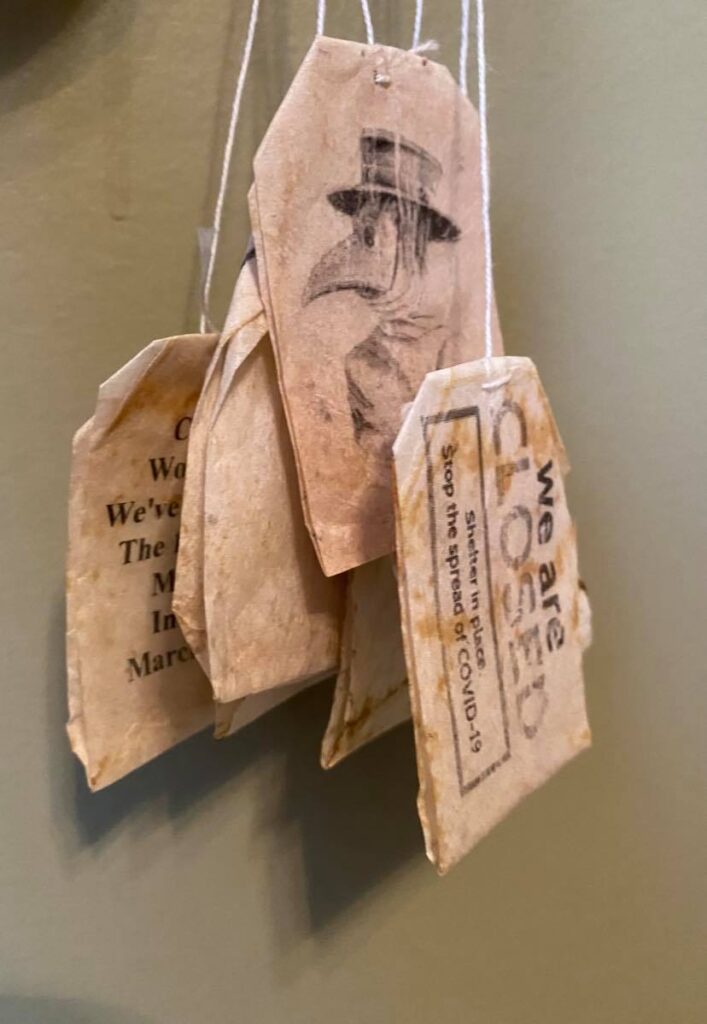

Daily Cup of Covid

Daily Cup of Covid is a gathering of bits and pieces of the discourse of the covid-19 pandemic of the past year. In printing tea bags with slogans, images, and important dates from the pandemic, I am portraying the way in which such discourses have an impact our daily routines. Like our daily cups of tea (I would have used coffee but coffee does not come in lovely little packages!), the news of the pandemic has been delivered, has been poured into our daily perceptions and memories, has coated the lenses through which we have viewed the world. Routinely, almost to the point of banality, we have consumed this news, the reports, the statistics, day, after day, after day. We have measured out our life by the news of the pandemic.

And so, what does it mean to have our life measured out in this way, to have this event against which we assess our lives? Must we, like Prufrock, confront the incessant horror, the loneliness, the repetitiveness of the news and our new daily routines? Are we, like him, being asked daily to confront all that has not taken place or been realized during this time? One more day, one more day, one more coming and going. What kinds of conversation do we have, now, about Michelangelo?

In thinking about ways to represent the daily routine-ness that the pandemic has become, I considered the shape and smell and meaning of tea bags as a way to fracture the banality of the incessant reportage, while maintaining the repetitive feel of the news cycle of the past year. I am tapping into the uncanny effects of juxtaposing something entirely ordinary, the “heimlich”, the comfort of tea, with news of the extraordinary, the “unheimlich,” of the pandemic, as well as creating a memorialization of the past year’s daily experiences.[1]

The tea bags themselves are made of a delicate, ephemeral material that reflects the temporality of life. The natural staining of the fabric with tannin and other herbal properties from the tea immediately lends the fragile fabric a vintage feel that inspires us to feel nostalgia for times past. The pandemic has had a jarring effect on the experience of the passage of time, partly due to the disruptions in daily routines, partly due to how long it has lasted. As a type of encounter with the unheimlich, the pandemic has affected a kind of temporal dissonance. The result is that the ‘time before the pandemic’ may feel at once further—remember when?—and not terribly distant—has it really been a year?—simultaneously. The nostalgia reveals the yearnings we probably all feel to be able to sit across from friends and share a cup of tea, in the crowded comfort of cafes and restaurants, a yearning even, for the feeling the closeness of strangers. Or to savour hours in close quarters in the homey comfort of a friend’s kitchen, talking away the evening, talking of nothing and everything at all. Most of our cups of tea for the past year have been taken in solitude. The tea bags are both solitude and communion.

The fragility of the tea bags, their gauzy, delicate weave, just barely containing the fragrant leaf fragments, point to our own fragility in the face of a disease that ravages our own flimsy, temporal existence. How easily our bodies succumb to the microscopic ravages of a virus running rampant across the globe. How many of us have wondered whether or not we would be strong enough to fight off its ravages should we become infected? How many of us have suffered its ravaging effects, watched or heard of loved ones succumbing?

The pandemic has meant many losses, including our ways of amusing ourselves. It has meant sacrificing, or at the very least putting on hold, goals and projects. Many of us may have gotten through the pandemic so far, by assuring ourselves that this little disruption is ok; it is just a few weeks, after all, a few months… a year, now more. And like Prufrock, we may find ourselves, as we suppress the anxiety of missing out, of not doing the things we love and had planned for, repeating that “indeed, there will be time,” there will be time. But this time period is not just an interlude, and pause, a refreshment break during the opera. This time has meaning, too, in the story that is our lives.

Daily Cup of Covid conceptualizes a way in which we processes events as they are unfolding, as bits and pieces of texts, of information that we take into ourselves and digest, rearrange and make meaningful. It also takes that act of processing, of examining the way in which the by-products of media have become something we consume, or that consumes us, whether we want them to or not: the pervasive presence of media and hyper-communication in a media-defined world, a world framed by Facebook and Instagram photos, the endless scrollings of the records of daily activities, a news cycle that never ends. Just as we set up our digital universe to alert us, or deliver to us daily, the news, we sit and take our daily cups of tea. Often the latter is interrupted, or occurs simultaneously with the former—how many of us read the news while sipping a beverage? Is it even possible to sip a beverage without also, at the same time, reading something on our smart phones or tablets or laptops— or newspapers? This teabag conceptualization seeks to mimic and disrupt that process.

Ideally, this collection would be displayed so that viewers could interact with the tea bags in a tactile manner—in real life—for the teabags’ tactility is very much the centre of the aesthetic and sensory aim of this project. The tea bag’s own fragility, the softness of the material, the scent of the tea that lingers, along with the traces of natural dye on the tiny bags is integral to the experience of this display. The action of touching, of rifling through a box of tea, searching for the exact taste one is looking for, is key to the experience of tea drinking. Of course, due to Covid-19’s on going impact on our health and safety (oh! How many times have we heard this?!?!), this is not possible at this time. Maybe one day, this can happen. Alternatively, many of us have pondered the possibility that gathering in public spheres as we once did, to mingle, to weave ourselves through spaces filled with strangers in close quarters, to touch things that others have touched, the very thing that many of us desperately miss, may be a thing of a the past. [2] This is also a love letter to that past, a promise of a kiss in the future. And so, we must invent new ways of creating and sharing the experience of art and culture, sharing our cups of tea.

Not knowing when it would be possible to present the collection in real life, I decided that I would create a digital experience, pale in comparison, I’m sure, in order not to miss the time-sensitive opportunity to share my ongoing thinking about how and what we will remember from this time, and how those memories are shaped and preserved. It is generally accepted in anthropology and sociology, that objects, our material culture, carry meaning and communicate the values and beliefs of the people who created and used those objects, and that their very design can also reflect those values and beliefs.[3] Certainly tea bags carry myriad values and beliefs, customs, rituals, and tea’s identity and history is fraught with colonialism, imperialism, environmental concerns, class divisions, warfare, and international trade. It is already culturally loaded. It is derived from a plant that grows only in certain parts of the world, and yet it is consumed widely, and has been a core commodity of international trade dating back hundreds, even thousands of years. Approximately 5000 years ago, or so the stories go, tea is first mentioned in the written historical record in China, when some leaves from a tea plant blew into emperor Shen Nung’s cup of hot water[4], and since then it has been valued, traded for, and fought over. It has been consumed in all manner of style, from workers taking their tea break on factory floors in crude vessels with dirty hands, to highly codified and elaborate ceremonies, as well as for its medicinal and soothing, uplifting properties.

The accoutrements of tea-making have a long and aesthetic history: the teapots and cups, the various vessels for the brewing of tea, loose leaf, or more recently in bags, teaspoons, tea balls, and various strainers, slices of lemon, or not. Bagging tea in delicate packages of fabric or paper, is a relatively new innovation, just over a century old now, and very much part and parcel of the early 20th century proclivity towards convenience: the tea bags enabled tea drinkers to easily and without much mess remove the tea leaves from their cups when their tea had reach their preferred state of brewing. Previously, one either left the leaves in one’s cup, or pot, or strained the leaves through sometimes elaborately designed strainers. It was also an efficient way to distribute single cups of tea in the burgeoning café culture of Europe. In any case, the way in which tea had been brewed for thousands of years was radically altered with the invention of tea bags and reflects the growing pressures of the need for convenience and speed, and a different kind of commercial viability as single servings.

The tea bags themselves have taken a variety of shapes, sometimes looking like little silk pouches, and at other times wrapped in what looks like a little envelope, shaped like a house, at least to me, and therefore bidding a heimlich, or homey feeling: comfort. I have played with this subjective and suggestive shape to cause some discomfort alongside the banality. We’ve all been feeling it anyway.

I have intentionally left them a bit “dirty,” as in, there are specs of tea leaves still in the bags, for instance. There is much to- do made about hygiene these days. Various writers have invoked terms such as “hygiene theatre,” or “performative hygiene” to describe the way in which we have sought on a practical level, to cope with the invisible (to the naked eye) contagion of the Corona virus. Indeed, we have likely all witnessed the extraordinary rituals of cleanliness—the wiping down of surfaces, the sanitizing of hands—or have read that businesses and places of work are “deep cleaning” after having been alerted of an outbreak, as if we can simply wash the virus away, kill it with hand-sanitizer and Clorox wipes. My tea bags, on the other hand, are meant to look a bit grubby, used, consumed. They are meant to recall a more carefree time, and more natural relationship with ourselves and each other, unmediated by sanitation efforts. In their sepia-tones, which suggest the accumulation of time and experience, they are meant to grub-ify our imaginations of the notion that unclean equals deadly, that we, as humans, are unclean and germ-ridden, dangerous. It is an attempt to reclaim our natural humanity even as we seek to contain the virus; we must not fear our own and other’s humanity. We are not the virus.

“It takes a certain amount of time and distance to fully see and understand art that comes from a crisis,” says Jessica Beck, The Warhol’s Milton Fine Curator of Art. “Just as it takes that kind of time and distance for us to understand what took place during that crisis, whether it was a war or a health or economic depression event.”[5] This is true in the sense that we cannot fully understand the breadth and depth of the impact of an event such as a global pandemic until it is over, and the final tallies of sick and dead are in, and the economic toll, the psychological toll can be assessed. Nevertheless, as we move through a crisis, we are in a constant state of assessment of our day- to- day well-being—and not just of our physical health— but also as our understanding of the situation as it develops, as it drags on. This is why I feel like it is important not to wait until it is over, but to examine what is happening now: how do we feel now? What am I thinking about now? To track the experience—what we feel after one week, one month, six months, a year or more will certainly evolve, and our artistic responses will evolve with the passage of time. What are we feeling now during the case surges, surely, but also during the lulls, while we wait to see where the pandemic goes and what it does next. Daily Cup of Covid is an attempt to capture the daily experience, the as-it’s-happening impression of what it is like to live through a global pandemic: the startling and the mundane.

Looking at back at the 1918 Influenza epidemic, I can see that it is not clear that artists were widely grappling with ways in which to depict the horror of the illness that claimed so many lives. Many critics and historians of the period have suggested that there was little art that came out of the period pertaining to the global health epidemic because it coincided with the end of World War I. The conflation of these events means that the art reflects a more complex situation that would itself go on to produce a rich modernist aesthetic period, but did not necessarily address the epidemic specifically. Two artists in the fine art scene stand out as having engaged directly with the epidemic: Edvard Munch[6], who contracted the flu and recovered, and Egon Schiele[7] who contracted the flu, and perished just days after his wife succumbed. [8] Additionally, the Dada-ist and Bauhaus movements are generally credited with presenting an aesthetic that responds to the need for more hygienic designs, as well as an impulse to make sense of the turbulent post-war period. [9] For the most part, it seems, the 1918 Influenza epidemic did not inspire many artistic reactions or depictions. It is almost as if everyone who survived simply wanted to forget—forget the illness, forget the war—and carry on with living.

There have been other epidemics in our living memory, of course, including Ebola, AIDS, and another SARS outbreak previous to Covid-19. Of the 1918 pandemic, it has been theorized that there are “virtually no monuments or memorials to those who died from influenza in 1918–19, in part because of the contemporaneity of the war, but also because the pandemic seems to have lacked any central organizing visual motifs.”[10] In contrast, the AIDS epidemic has produced the richest body of artistic response to the impact it had on various communities and individuals to date.[11] I would hazard to say that the rich artistic record is largely responsible for encouraging the ongoing scientific work that has lead to effective treatment for AIDS patients, and for reducing the stigma towards AIDS patients. The artistic response is a monument to the dead and living, the survivors and the victims and underwrites much of the social understanding of the AIDS epidemic.

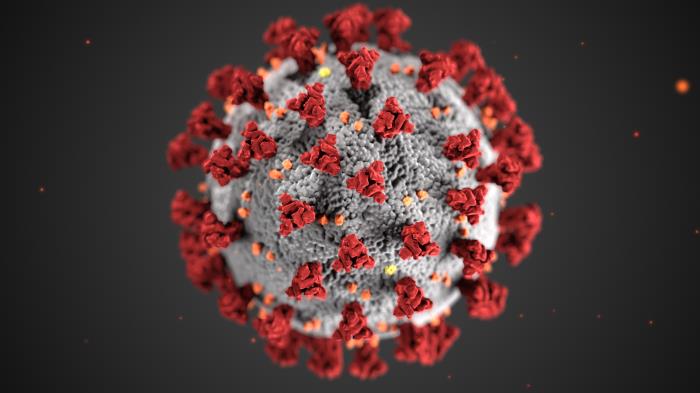

The Covid-19 epidemic, has perhaps drawn upon the effectiveness of the artistic response to the height of the AIDS emergency, after all it has taught has so much about our fragility and our resilience. Although the full impact will remain to be seen until the pandemic is over, the artistic response to Covid-19 has already produced a plethora of artistic creations and visual responses to the pandemic during the first year, in part, I would assert, due to the early creation and shareability of images digitally through social media. Additionally, a graphic rendering of the virus in an image as a sphere with protruding spikes was created early in the pandemic and is widely recognizable. Furthermore, during the Covid-19 pandemic, we have broadly drawn comparisons to the Decameron, for inspirations and many creative collectives have arisen as a response to the global pandemic, as a means of creating an artistic record of the experience of the pandemic itself. [12]

With Daily Cup of Covid, I seek to participate in this artistic response to the pandemic with this meditation on the epidemic’s impact on our day-to-day experience, as well as offer a record, a souvenir of this time-period and the experience. It is a memory piece that draws upon the innate ability of our material culture to affect how we remember. As Andrew Jones has noted, objects help societies remember [13] and most certainly, we need not only to remember the facts and statistics, the scientific data relating to pandemic, but its effect on people. Our collected and preserved memories will later allow us the benefit of analysis from a distance. Here, John Locke’s 17th century notion of memory as a type of storehouse, not only persists as the manner in which we conceptualize memory, but is still the dominant way in which we envision our memory making: as if we can take memories and put them somewhere in our brain, take them out when required. Of course, modern neuroscience has explained that it is much more complex than that, but the metaphor for a layperson’s understanding of memory-making is still relevant. [14]

Of course, objects can serve as triggers for memory, even when there is a lack of one to one correspondence between the object and the memory itself. This notion was explored most famously in Marcel Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu, a novel which is entirely brought on by an encounter with an madeleine. Here, an object is presented as stimulus for involuntarily eliciting our memories. How many of us have experienced this, in particular with food, or a certain smell, a texture, or a sound, or song that rather than being directly associated with a person, or event, encapsulates the mood or emotions and therefore attaches itself to a person or event? The aroma of Earl Grey tea will always remind me of a friend, now deceased; oddly, I can only recall drinking tea in their company just once in our 25 year friendship—it was always coffee—and yet, the singular exception persists as a gateway to memories.

Additionally, we are collectors of souvenirs, of trinkets and baubles that serve to remind us of where we have been, what we have accomplished. We treasure the gifts we have received from friends and loved ones. We are commemorators, who often use objects to symbolize and remind us of significant events, often long past, sometimes even beyond our own life spans. We erect memorials, place wreaths, arrange flowers, wear buttons and ribbons, we place plaques in memory of, we draw family trees, and enter the births and deaths in records, we create scrapbooks and photo albums, and we celebrate anniversaries and birthdays; we keep mementos. We do this, for despite our desire to conceptualize our own memories as objective, infallible even (but I remember such-and-such happened!), sometimes our memories fail, or fill in missing details. We may remember an event, or a person, but we also add interpretation to our memories and our experiences,[15] and this makes our perception of what happened very subjective, personal, fallible. We like narratives that are complete, logical. We despair when we realize that we cannot remember something or someone. When the authenticity of what we remember is called into question, so is the very act of remembering. And so, we invent different ways to remember. This is my invention.

I hope you have enjoyed Daily Cup of Covid.

To Gallery

[1] In 1919, Freud detailed in his famous essay, “Unheimlich” the concept of the uncanny, “undoubtedly related to what is frightening — to what arouses dread and horror; equally certainly, too, the word is not always used in a clearly definable sense, so that it tends to coincide with what excites fear in general.” https://web.archive.org/web/20110714192553/http://www-rohan.sdsu.edu/~amtower/uncanny.html

[2] https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2020/08/coronavirus-will-never-go-away/614860/

[3] See Steven Lubar and W. David Kingery. History from Things: Essays on material Culture. Smithsonian Insitution Press: Washing and London, 1993.

[4] http://www.china.org.cn/learning_chinese/Chinese_tea/2011-07/15/content_22999489.htm

[5] https://carnegiemuseums.org/carnegie-magazine/summer-2020/art-in-the-time-of-crisis/

[6] https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Edvard_Munch_-_Self-Portrait_with_the_Spanish_Flu_(1919).jpg

[7] https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Schiele_-_Edith_Schiele_sterbend_-_1918.jpg

[8] https://carnegiemuseums.org/carnegie-magazine/summer-2020/art-in-the-time-of-crisis/

[9] https://time.com/5827561/1918-flu-art/

[10] https://www.artforum.com/slant/michael-lobel-on-art-and-the-1918-flu-pandemic-82772

[11] https://www.artspace.com/magazine/news_events/exhibitions/8-iconic-aids-activist-artworks-that-changed-the-trajectory-of-the-epidemic-56088

[12] https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2020/lifestyle/coronavirus-pandemic-love-photos-1/?fbclid=IwAR3H02arpKrwZ9LV5X8jxV1OPzTvQdEDl5nZt4tlARFWto1YpzvU669V3FA ; https://www.anewdecameron.com/ ; https://www.patreon.com/projectdecameron ; https://www.patreon.com/projectdecameron ; https://thepolyphony.org/2020/06/16/art-in-isolation-artistic-responses-to-covid-19/ ; https://rsc-src.ca/en/themes/artistic-responses-to-covid-19 ; https://robbreport.com/shelter/art-collectibles/gallery/contemporary-artists-covid-19-new-works-2911980/cleanlinessisclosetogodliness111/ ; https://greetingsfromisolation.com/about-the-collection/?fbclid=IwAR0EK_dKhmo8fVOENotYtxtfMvYwl6GEGX9nmuLdLedghFmyqYuI2JIcuJg#:~:text=Created%20by%20Canadian%20veteran%20film,a%20capsule%20collection%20film%20project , as examples.

[13] Alex Jones. Memory and Material Culture. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2007 (5).

[14] John Locke, An essay concerning human understanding. Penguin: London, 1997 (1690).

[15] J. Fentress and C. Wickham. Social Memory. Blackwell: Oxford, 1992.

*All images are the original creation of Jolene Armstrong, 2021. They would not have come into existence without the marvelous support, laughs, friendship, and encouragement of the Decameron 2.0 Collective.